How Researchers are Returning Sensation to Mastectomy Patients

The Bionic Breast Project is an interdisciplinary research program applying bionic technologies to restore post-mastectomy breast function.

The Bionic Breast Project is an interdisciplinary research program applying bionic technologies to restore post-mastectomy breast function.

Leading the project is Stacy Lindau, MD, MA ’02, a Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Medicine-Geriatrics at the University of Chicago, and director of a research lab in the Biological Sciences Division at the University. She also is the founder and chief innovation officer of NowPow, a personalized community referral platform to support whole-person care. According to Lindau, about half of her patients over the last decade – which is now several hundreds of women – have had breast cancer and express new difficulties with sexual function during and after breast cancer treatment.

“One of the common problems women complain of is the loss of sensation in their breast after mastectomy with reconstruction,” explained Lindau, noting that even women who have a lumpectomy with radiation often cite changes to sensation in their breast that interferes with their sexual function.

Motivated to work on the problems her patients need solved, Lindau set out looking for evidenced-based solutions to these problems and came up empty-handed. She also learned how little attention is paid to the functioning of the female breast beyond its role in breastfeeding or lactation.

“It was with these observations and substantial suffering among my patients that I went looking for a solution to the problem of lost sensation and more generally, loss of function in the female breast in the context of breast cancer,” Lindau said.

In looking for answers, she came across media stories about successes with penile transplants, of which there have been five globally to date. What struck her about this coverage was the rarity of the conditions that would warrant this transplant, in relation to the significant investment that has been made in restoring penile function. Additionally, Lindau said she was struck – and given hope – by the fact that the success of these procedures was being judged not just by the cosmetic appearance, but also by three aspects of penile function: urinary, sexual, and reproductive function.

“In the US alone, 100,000 women a year have one or both breasts removed. That’s a lot of women losing an important body part. We should envision and find a solution for women that not only restores the appearance of the lost breast, but also the functioning of her breast for social and sexual and even reproductive purposes,” said Lindau.

Advances in bionics emerged as a good place to look and Lindau quickly connected with Sliman Bensmaia, whose work in the field was previously highlighted by former President Barack Obama.

Sliman Bensmaia photographed at the Anatomy Building for the University of Chicago February 11, 2014. (Photo by Jason Smith)

Bensmaia, PhD, UChicago James and Karen Frank Family Professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy, said the project dovetails nicely with his previous work – but the target population is much larger.

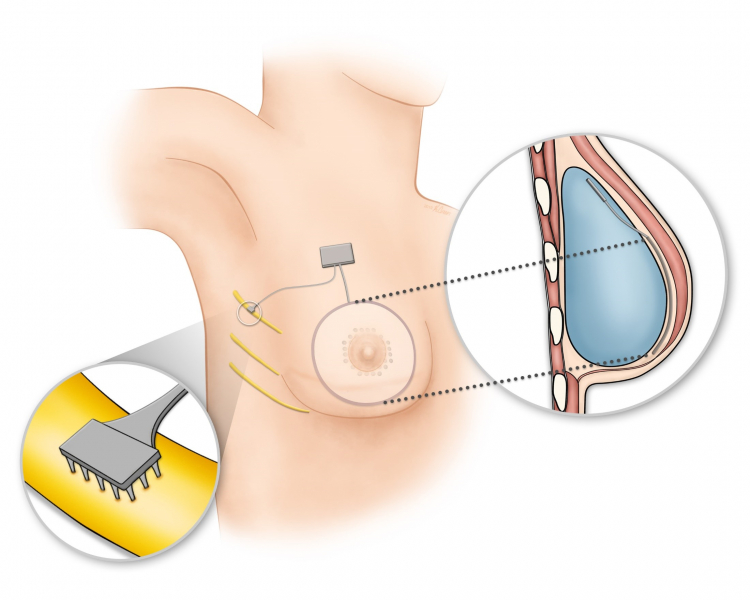

Using some of the concepts developed for the bionic hand, the researchers plan to embed a flexible sensor array under the skin of mastectomy patients. Activated any time the nipple-areolar complex is touched, the sensor array sends signals to a series of electrodes that stimulate the patient’s residual intercostal nerves – nerves that used to interface with the breast.

“You can create vivid sensations of touch by electrically activating the nerves of the hand,” explained Bensmaia, noting that the Bionic Breast will foster re-embodiment of the patient’s chest. “It can feel like a part of their body again,” he said.

Schematic illustration of the Bionic Breast concept for a breast reconstructed using an implant.

UChicago has filed a patent application related to the work, which is backed by the National Cancer Institute R21 grant mechanism. The grant is intended to encourage exploratory research and gives the researchers two years to establish a working relationship and do the foundational and development work needed to warrant a longer-term, larger-scale investment.

As part of this, the researchers also are collating a list of subjective and objective criteria by which to measure breast function. “If we want to study the relationship between breast cancer treatment and breast function we need a measure to assess breast function – and that did not exist,” said Lindau, whose lab is leading this work with input from a patient advisory board that has been helping define the right questions to ask and the right people with which to collaborate.

The testing rig is an adaptation of the one Bensmaia’s team used in their work studying hand sensation. It enables the researchers to precisely quantify sensory perception in the breast.

While Lindau’s team is well on its way to developing a measure that can also be used by others, Bensmaia is in parallel conducting the physical testing to quantify breast sensation. His team has developed a rig that enables the researchers to precisely quantify sensory perception in the breast, which Lindau has affectionately dubbed the ‘booby trap.’ The device is an adaptation of the one Bensmaia’s team used in their work studying hand sensation.

Testing the sensor technology subcutaneously for an extended period of time is the last technology development piece left to complete. Sihong Wang, PhD, an assistant professor at the UChicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering, is developing the tissue-like pressure sensors that can be structurally and functionally integrated into the Bionic Breast.

“Such sensors can work similarly as the sensing receptors in the breast for sensing physical contact/movement, by converting it to an electrical signal,” said Wang. “Our major steps are to build such sensors with tissue-like soft materials that are biocompatible for implantation, and to use the electrical signal to communicate with the artificial peripheral neural devices that Sliman will build.”

Mastectomy and reconstruction often happen in multiple stages, during which the researchers can implement the sensor array, giving them the opportunity to prototype without subjecting patients to additional surgeries. “It’s much less invasive than bionic hands, which require a special surgery to make that work,” said Bensmaia.

The researchers also plan to apply for an additional grant, which will help lay the foundation for studies in animal models and humans.

“This has the clearest path forward in just about anything I’ve ever done. All the components are in place,” said Bensmaia. “I am very confident this is going to work and help millions of women around the world.”

The researchers worked with the Polsky Center to file a patent application for the technology, which was discussed in a peer-reviewed article today published in Frontiers in Neurorobotics.