DeepTechU Day 2: Securing VC Funding and Federal Grants that ‘Take on the Risk that the Private Market Cannot’

The second day of DeepTechU featured practical advice for deep tech startups seeking funding, including when to start conversations with venture capitalists and how to use federal government grants to get investor ready.

But first, Bill Jackson, executive director of Discovery Partners Institute, delivered introductory remarks highlighting the strength of the deep tech ecosystem in the Chicago area, where an array of institutions are working together to meld science, engineering, business, and design thinking to create opportunities for deep tech ventures.

“We are creating this ecosystem not to compete but to cooperate in order to win,” said Jackson, who runs the University of Illinois-led initiative to grow tech talent, applied research, and business in Chicago. Deep tech, Jackson added, “is the future” and “will be core to Illinois and particularly Chicago.”

For startups driving the deep tech innovations of the future, the long runway before revenue makes raising money a particularly challenging endurance sport.

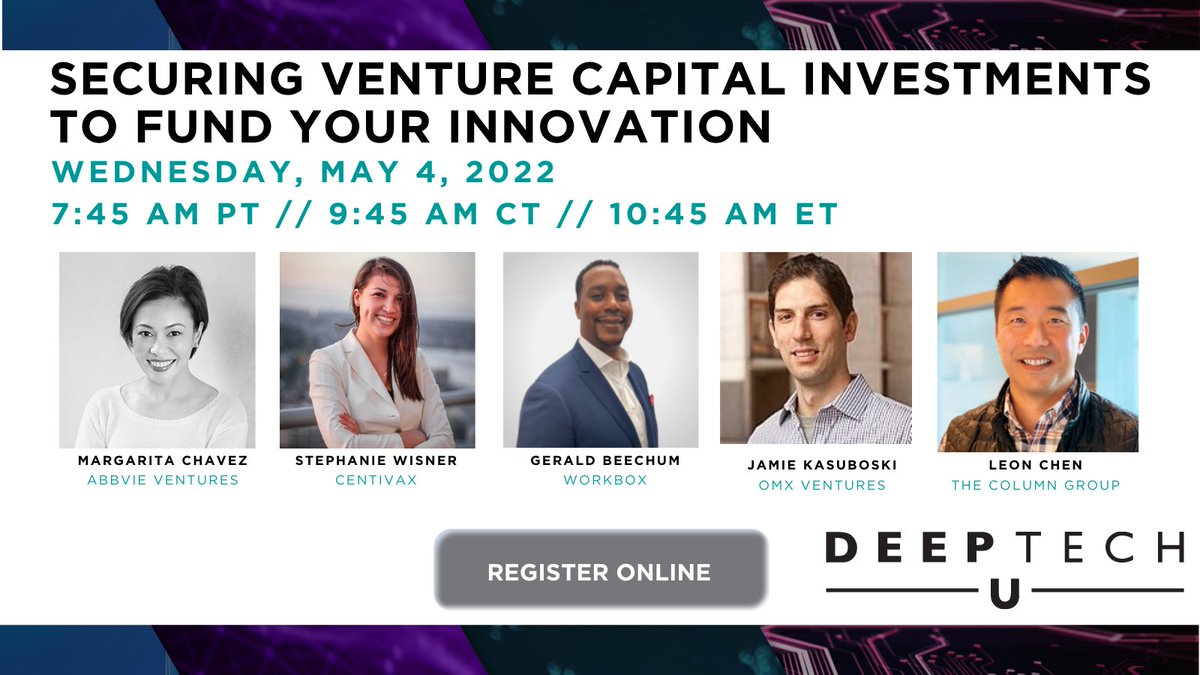

During a panel discussion on “Securing Venture Capital Investments to Fund Your Innovation,” moderator Margarita Chavez, managing director at AbbVie Ventures, asked the panelists at what stage of a startup’s evolution should innovators start engaging with VCs.

Jamie Kasuboski, an investor with OMX Ventures, said he likes to see “at least some traction on the science” and a “generalized proof of concept.” Its portfolio companies tend to be three or four years away of getting their innovations into clinical use, and at least a couple additional years away from generating revenue, so the technical potential of the science is of foremost concern.

Gerald Beechum, managing director of White Cornus Lane Investments, said it is never too early to talk to investors, largely because they can guide founders on what they need to solve for and what metrics they should be hitting. He looks for companies that at least have a business concept, which should be well thought-out before founders trot out a pitch deck.

Stephanie Wisner, MBA ‘20, co-founder of Centivax, a startup developing broad-spectrum vaccines against infectious diseases, suggests founders approach VCs under the premise of seeking advice, not money, so they can make a good first impression even if they are not yet ready with a business presentation.

For Leon Chen, partner at Collum Group, an early-stage healthcare investor, researchers should start the VC conversations early and not worry about the business side. His company does not expect founders to have any business plan in place, and focuses its discussions on the basic science the researchers are working on. Chen’s firm writes the business plans and pitch decks for 80% to 90% of its companies and helps them recruit and hire the executives to build a for-profit company.

“Our perspective is that you don’t need traditional business oversight,” Chen said. “What you need is the best scientific organization. You can hire a full-time CEO much later.”

Bringing deep tech innovations to market is “a marathon,” Kasuboski said, so startups must pace themselves by targeting milestone markers specific to their ventures.

Wisner urges founders to map out their startup’s “value inflection points” – important milestones that de-risk the company enough to put it in a better position for additional funding. For Centivax, she has found investors care a lot about how much time it will take to get to Phase I or II human data and how much it will cost to structure manufacturing to produce enough drug product.

“Think about the value inflection points and think about them early,” Wisner said.

A key tool to getting a deep tech startup to the next inflection point is finding funding through federal grants, including Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) grants. The second panel discussion of the day, “Securing SBIR/STTR Before, During, and After Equity Capital,” moderated by Pat Dillon of the Minnesota SBIR/STTR Accelerator, focused on how startups can use those federal funds as a bridge to attract venture capital.

“SBIR can get you across Valley of Death to de-risk and get money from outsiders,” said Becky Aistrup, managing partner at BBC Entrepreneurial Training and Consulting.

Through the SBIR program, 11 federal agencies allocate a total of $4 billion in grants annually to research-based startups, many of which are based at universities. Nearly half of the ventures funded each year are new to the program, which focuses on long-term projects that VC and angel investors are unwilling to fund, said John Williams, director of innovation and technology at the Small Business Administration, which oversees the SBIR program.

Anna Lisa Somera, CEO of the medical device startup Rhaeos and an SBIR/STTR grant mentor at Argonne National Laboratory, said startups should make a commercialization timeline and plan out how federal grants can help them get from one milestone to the next.

“Think of each of these funding mechanisms as a way to hit those milestones,” she said. “Because that will resonate with investors.”

Indeed, said Josh Nichol-Caddy, technology commercialization director at the University of Nebraska, landing SBIR funding is an important proof point for investors.

“Invest Nebraska loves to invest in SBIR companies because they have already been evaluated,” Nichol-Caddy said.

Still, the panelists cautioned startups that giving up too much equity to outside investors could disqualify them from future SBIR funding in some cases.

To conclude the morning sessions, the National Science Foundation’s Andrea Belz delivered a keynote presentation on the economic importance of science-based startups, which are engines of job creation. Some 30% of the Nasdaq’s value originated at university-based federally funded research projects, she said.

She also expressed concerns about the shifting landscape.

Despite enthusiasm about startups, the rate of startup formation has declined over the last 40 years, and in some sectors venture capital investment has not fully recovered since the dot-com bust, Belz said. Investors are also looking for greater certainty early on, with two-thirds of seed-stage companies today already generating revenue compared to just 9% a decade ago.

“The appetite for risk has changed,” said Belz, director at the NSF’s division for translational impacts. There is a need for more funding at a startup’s early stage, she said. In addition, while universities do the bulk of basic research, and industry dominates development research, there is a gap when it comes to applied research.

NSF programs help plug some of those gaps. Companies that received the agency’s SBIR grants have gone on to raise $14 billion in follow-on funding and achieved more than 200 successful exits.

The seven-week I-Corps program, which trains innovators in customer discovery and offers $50,000 in grants, has funded 2,000 teams to date, half of which went to on to start companies that raised $500 million in follow-on funding.

“We are taking on the risk that the private market cannot,” Belz said. She added: “Need for these programs is probably greater than ever.”