Entrepreneurship in Africa Has “Big Risks” and “Big Payoffs.” Here’s How Ugandan Businessman Aga Sekalala Jr. Found Success.

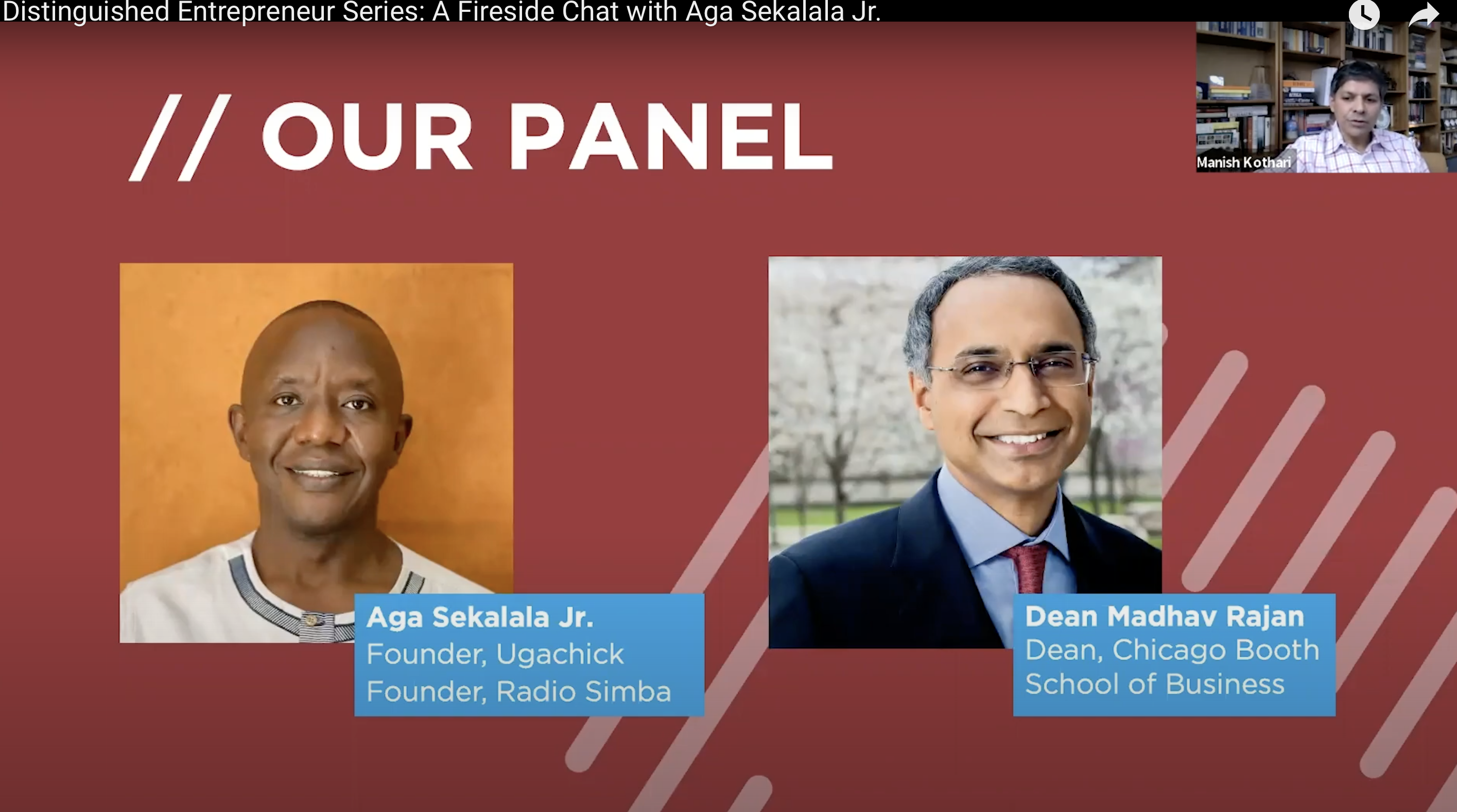

The Polsky Center’s Distinguished Entrepreneur speaker series this month featured Aga Sekalala Jr., a prominent Ugandan businessman who founded Radio Simba, one of the most popular broadcasters in East Africa, and whose family runs one of the nation’s largest poultry operations.

In an interview with Chicago Booth Dean Madhav Rajan, Sekalala discussed why those ventures were good bets, how he’s navigated the talent and regulatory hurdles of doing business in a developing country, and what he thinks are the best opportunities for investment in Africa.

“There are big chances, big risks, and there will be big payoffs for those who get it right,” Sekalala said.

Watch here and read below for a recap.

From engineering to chicken to radio

Uganda was at war when Sekalala finished secondary school, prompting his family to send him to the U.S. for college, where he received a degree in chemical engineering from University of New Mexico. Sekalala credits the international exposure with shaping the risks he took as an entrepreneur, as he saw business models he wouldn’t have imagined possible back home.

Upon his return to Uganda, Sekalala and his father founded Ugachick Poultry Breeders, which sells day-old chicks to local commercial farmers. The company, which operates chick and broiler farms, feed mills and a processing plant, localized a product that traditionally had been air-freighted in from Europe, Asia, or South Africa.

“Most businesses in this part of world … start as import substitution,” he said.

Founded in 1992, Ugachick was a risk in a country just emerging from war, where incomes were low and people were accustomed to eating chicken only during festive occasions like Christmas and Easter. Encouraging Ugandans to eat poultry more regularly has been as important as production, and consumption – through it remains very low – has grown consistently.

Sekalala launched his next venture while taking a sabbatical from the family business. At the time, Uganda was liberalizing the airwaves after many years of permitting only national broadcasters, offering five licenses nationwide on a first-come, first-served basis

To many people, commercial radio didn’t make sense as a business opportunity. Who would want to advertise?

But Sekalala had seen it work in the U.S., and knew that if he had an audience he would have advertisers. He and a friend applied for one of the licenses, found three investors to fund equipment and a studio, and in 1996 Radio Simba went on air.

The company, which played music targeted at local communities, grew to have two brands in Uganda and numerous stations from Kampala to Kenya. Sekalala ran it until 2010, when he sold the Kenyan properties and stepped down as CEO to rejoin Ugachick as his father moved toward retirement.

Working with family can have challenging dynamics, but Sekalala, who enjoys operations, and his father, who has relationships with small farmers, brought complementary skillsets. And in Africa, family businesses are the standard and tend to have the best reputations.

That’s in part because talent, and particularly managerial talent, is not as available as it is in more developed markets, so families make good teams.

“Family is easy to work with in terms of trust and loyalty and being able to make long-term plans,” Sekalala said. “If family is involved, you accumulate more capital, relationships, networks. These groups are the go-to, even when an external player wants to come into the market they will partner with them. It’s become the safe bet, really.”

Opportunity in “the basics”

Talent has become easier to find in recent years. Improvements to local schools and training institutes have allowed Ugandans to upskill, while upgrades to infrastructure and quality of life are attracting skilled workers from South Africa, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Egypt, and other African countries. In addition, more Ugandans are studying and working abroad and bringing that experience back home.

Still, talent has not kept up with Uganda’s growth, which has been in the double digits most years over the past two decades.

The greatest areas of growth in Africa, with the greatest entrepreneurial potential, are in “the basics,” Sekalala said.

Much of the population remains low income and works hard to afford two meals a day, little by little eating more chicken and bread and aspiring to have clean water and housing they can call their own.

“There is quite a lot of opportunity in the basic things,” Sekalala said. Entrepreneurs should target small, local markets, and “be ready to play in the long term because clearly these markets take time.”

Sekalala is now an investor in African startups and active mentor to young entrepreneurs, dispensing advice learned from experience.

One of the key lessons is the value of working together with competitors to navigate restrictive government policies and advocate for common issues.

“Have cohesion among players and speak as a common voice,” said Sekalala, wo served as chairman of the National Association of Broadcasters and the Poultry Association of Uganda, among other trade groups. “So that it becomes easier to speak to the people who matter and they take your voice more seriously.”

Sekala made business mistakes along the way. Asked what he would have done differently as an entrepreneur, Sekala said he would have invested in stronger teams earlier on to keep pace with the growth of the market.

“I would have considered my team’s managerial knowledge as a capital investment as opposed to thinking of it as an operating cost,” he said.

He also questions whether engineering is the best preparation for a startup leader. It tends to be a study “with a big emphasis on limits” that encourages working “within the realm of possibility,” so engineers can’t always wrap their minds around entrepreneurial opportunities, he said.

Still, there are benefits of the discipline for entrepreneurs. Engineers approach challenges through the lens of science and know how to interrogate numbers to discover what’s behind them.

“This has served me well,” Sekalala said. “I am always ready to learn and I think that is one of the things in the study of engineering, is that you need to be ready to learn something and accept that you don’t know everything and be ready to pick it up from where you picked it up and try and make the best of it.”