Will the “Golden Age” of Tech Investment Last? Three Venture Capitalists Dive In During a Conversation Moderated by the Polsky Center’s Steve Kaplan

By all measures, 2021 has been a banner year for tech investment and returns. And money increasingly is flowing into markets like Chicago, thanks in part to a remote business environment that is encouraging venture capitalists to look between the coasts.

“It was a flyover city when it came to tech, in no uncertain terms,” Sach Chitnis, cofounder and partner at Chicago-based venture fund Jump Capital, said of Chicago’s pre-pandemic appeal to tech investors. “When people are not flying, they’re not flying over.”

But is the boom that is minting new unicorns daily going to last? And does the deluge of capital pose certain dangers?

Those were among the questions addressed during last week’s Sixth Annual Tech Outlook, a virtual panel discussion hosted by the Executives’ Club of Chicago exploring where the tech market is headed.

Chitnis, one of three early-stage venture capital investors feature on the panel, shared his insights alongside fellow panelists Mar Hershenson, cofounder and managing partner at Pearl Ventures in Palo Alto; and Dana Wright, managing partner at Chicago-based MATH Venture Partners. The conversation was moderated by Steve Kaplan, the Neubauer Family Distinguished Service Professor of Entrepreneurship and Finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and Kessenich E.P. Faculty Director of the Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

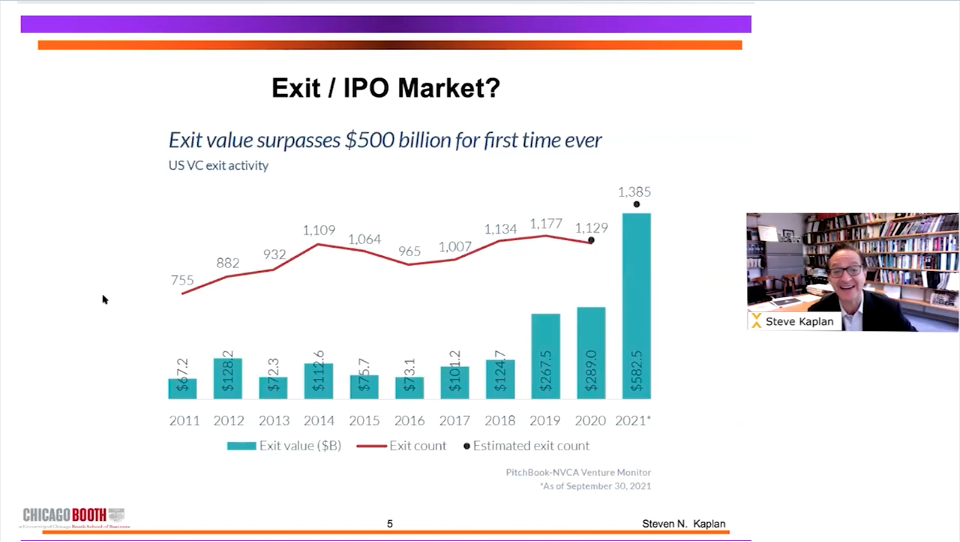

Kaplan set the stage by running through numbers that show stunning growth in deal value and returns.

“We are indeed in the middle of a golden age,” Kaplan said.

During the first three quarters of this year, venture capital investment in the U.S. reached $238.7 billion, up from $166.4 billion during all of last year, as the size of funding rounds ballooned. Exit values for tech startups, which have been climbing slowly since 2016, shot up to $582.5 billion in the first three quarters of 2021 compared with $289 billion achieved during all of last year.

Meanwhile, venture funds are seeing average internal rates of return of 40% per year, and investors even in median funds are making out better than they would have had they put their money into traditional index funds.

“What’s astonishing is… the average (venture) fund has been beating the S&P 500 by 60% to 100% over the last 10 years,” Kaplan said.

Public tech stocks also have far outperformed in the market, with the iShares Technology index up 75% since the start of January 2020 compared with a 36% rise in the S&P 500.

Chicago can claim a small but growing share of the gold rush. So far this year 12 Chicago-based tech startups have become unicorns – meaning they achieved a $1 billion valuation — raising the city’s total unicorn count to 20. Through the third quarter, Chicago area startups raised $5.5 billion, compared with less than $3 billion during all of 2020.

Chicago can attribute the growth in part to its concentration of transportation and logistics firms, which have become attractive investments amid global supply chain disruptions, as well as investments planted years ago now bearing fruit, said Wright of MATH.

But the pandemic-fueled shift to remote working has also erased geographic barriers and pushed investors to seek good founders with good solutions and metrics in all parts of the country and world, Chitnis said.

Hershenson said it is rare to have an in-person first meeting with a startup anymore, and a company’s headquarters matters less when Zoom backgrounds place founders at a beach in Hawaii or floating above a national park.

“That has made all of us in the Bay Area invest farther away from home,” Hershenson said.

Does that mean the Bay Area is going to be less dominant in venture capital? Kaplan asked.

“I don’t want to be on record for saying that,” Hershenson laughed. “Yeah for sure, we’re seeing that. It’s already happening. A lot of the venture money is still here, especially those big growth rounds, but it is spreading out, no doubt.”

Certain growth areas of tech have the VCs particularly excited.

Hershenson’s firm is investing in technologies tackling climate change, the evolving nature of work, and cryptocurrency.

“Which sounds crazy, but we made a decision about a year ago, we either get on the boat or we are going to be off the boat,” she said of the crypto craze, which she worries could be overhyped.

“It feels a little bit like the dot com right now in that space. It’s really out of control,” Hershenson said. “There will be great companies built, it’s just that everybody’s there.”

At MATH, investments tend to target companies focused on customer acquisition, and Wright said it is often wise to explore “unsexy” opportunities where others aren’t looking. The firm is also starting to look into Web 3.0 and the potential for a more distributed internet.

Jump is focused on technologies addressing banking relationships and shifts in consumption behaviors, plus it is making big investments in the infrastructure and enabling technologies of cryptocurrency.

“A lot of people say it will be the next internet, but that is diminishing it,” Chitnis said. “It will replace the financial system and capital markets.” Like with natural sciences and biotech, cryptocurrency investments are a long game, he said.

There are no signs yet that the influx of capital or pace of investment will slow. Investors that usually invest at later stages are coming in earlier and taking a “spray and pray” approach for Series B rounds, putting large amounts of money in multiple companies to create an index that spreads out their risk, Wright said.

That causes some worry, as many of these investors are not taking seats on the startups’ boards or helping them strategically. By getting so much money up front, rather than incrementally at proof points, founders may try to scale before they have solid unit economics, customer acquisition strategies and other building blocks for their companies, and will burn through a lot more capital, Wright said.

“Venture is more than money,” Wright said. “There is a lot of building that happens behind the scenes.”

The big money is causing other challenges for VCs. Picking companies is much harder than it was 10 years ago because investments are finalized faster, Hershenson said. With higher valuations come higher expectations and pressure to execute, Chitnis said. And everywhere there is a war for talent.

Still, the panelists are optimistic that betting on tech will yield success in the long term. Chitnis has found that his portfolio companies are using capital efficiently and hitting revenue targets earlier.

“If you are looking at where the opportunities for disruption are, are you betting on JPMorgan?” Chitnis said. “Or on JPMorgan buying these startups to really transform their industry?”