Celebrating Black in Tech: Insight and Advice from Black Startup Founders

Jasmine Shells, MBA ’21, founded her startup in Chicago with the intention of building it in Chicago as well. But when it came time to raise money, the checks were elusive. So she moved the company to New York, where venture dollars flow more freely.

She soon returned, however, determined to grow her business in a city that needs examples of Black founders succeeding and where the startup culture is increasingly devoted to helping its own.

“It has been so inspiring to see the commitment that Chicago founders have to Chicago,” said Shells, cofounder and CEO of Five to Nine, a management platform for workplace events and programs that she launched in 2019. “That’s one thing I will say I think is so different from the coasts, just in terms of the resilience and also the dedication that people have. People love this place. So I’m just excited to see how the support will continue to increase over time.”

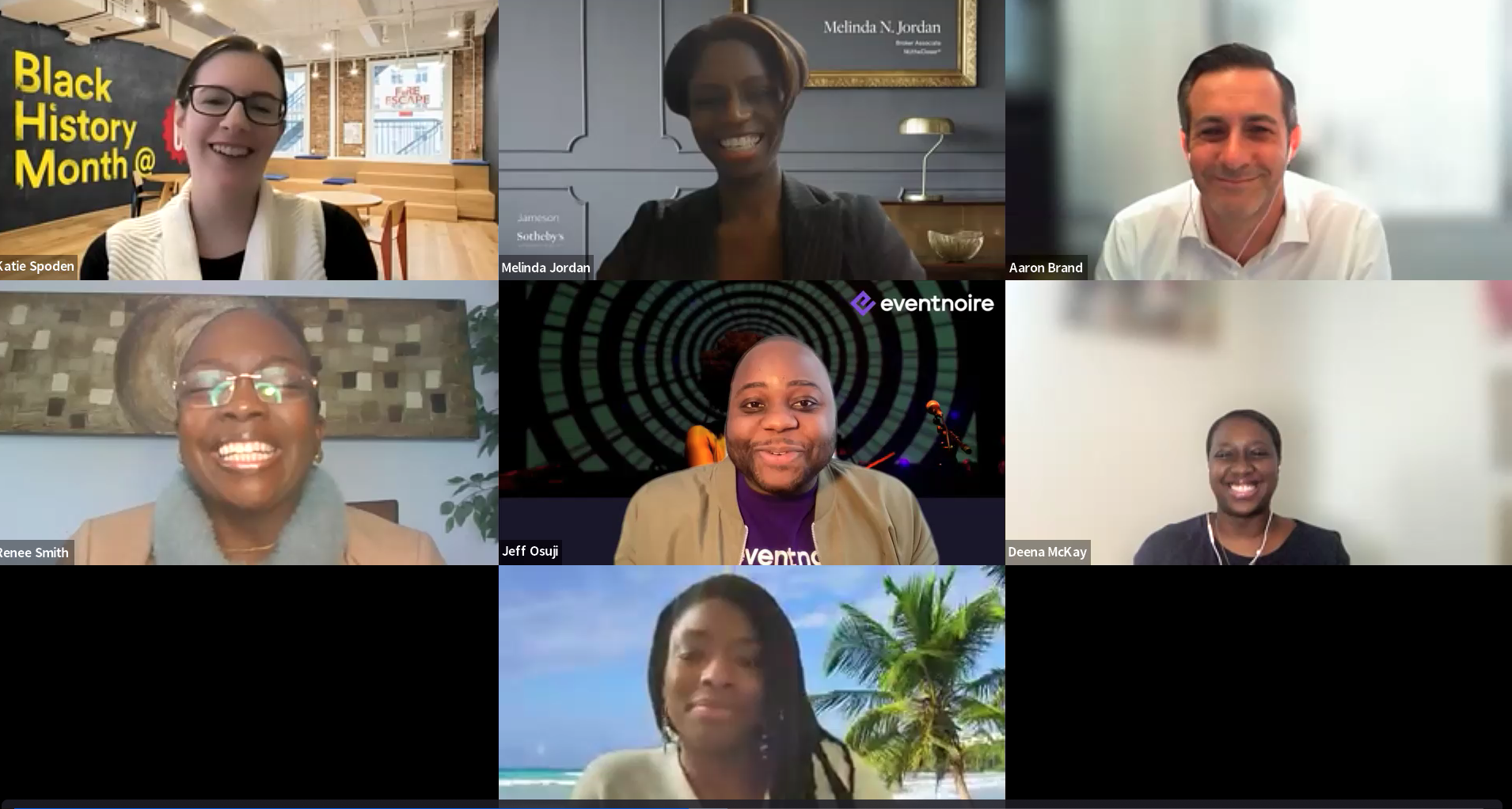

Shells shared her thoughts during a virtual panel discussion last week marking Black History Month. The event, Celebrating Black in Tech – Chicago Black Businesses, was hosted by General Assembly, a Chicago-based tech education company, in partnership with the Polsky Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation and the National Black MBA Association’s Chicago Chapter. National Black MBA, which has 40 chapters globally, started at the University of Chicago business school in the 1970s.

Black startup founders have been making significant inroads in the U.S. tech scene, but continue to face an uphill battle for capital – and, consequently, growth.

The amount of money flowing to Black entrepreneurs nearly quadrupled last year, to $4.2 billion, but that was still just 1.3% of venture dollars raised during the record fundraising year, according to Crunchbase. Funds focused on supporting Black founders have emerged to fight the disparity, but check-writers remain overwhelmingly white. As of 2020, just 4% of venture capital professionals were Black, according to Deloitte’s VC Human Capital Survey.

The Feb. 10 panel featured Shells along with Jeff Osuji, founder and CEO of Black culture ticketing platform Eventnoire, an alum of the Polsky Center’s Small Business Growth Program; Renee Smith, global senior director and Lean Six Sigma BlackBelt at Walgreens Boots Alliance; and Aaron Brand, head of new business at Founders First Capital Partners. It was moderated by Deena McKay, founder of the podcast Black Tech Unplugged and functional delivery lead at global consulting firm Kin + Carta.

The conversation topics ranged from the uniqueness of Chicago’s startup community to strategies for increasing hiring of Black tech talent.

Here are some highlights. A recording of the conversation is available here.

Keys to success

Asked to name the key factors that have contributed to their career success, the panelists offered several pearls of wisdom.

“Not being afraid to fail,” Smith said. “It’s about falling down and getting back up.”

“Putting your head down and just staying positive,” advised Brand. “Also networking. The people you talk to every day may be able to help you down the road. Keeping your relationships close and in good standing is of utmost importance.”

Osuji noted that when his parents immigrated to the U.S. from Nigeria, his mom worked at Burger King and his dad at McDonald’s while they put themselves through school. Eventually she became a nurse and he earned his Phd. Witnessing their struggle taught him the importance of hard work.

“It’s important to be humble, know where you come from, and really have discipline,” Osuji said.

Jasmine Shells

For Shells, a favorite piece of advice is to “learn on someone else’s dime.”

“Go work somewhere, learn from someone who has done it before,” said Shells, whose company placed fourth in the 2019 Edward L. Kaplan, ’71, New Venture Challenge. “I worked in consulting for some time and that helped me a ton. I learned a lot about business, how to manage relationships, how to manage up, how to inspire teams as a young leader.”

Recruiting Black tech talent

Companies committed to increasing Black representation in tech have numerous opportunities to put their resources to good use.

Shells encouraged companies to invest in programs to upskill or reskill career changers who may not have industry experience but can learn.

Corporations can also support accelerators working with minority founders by participating in pilot programs or offering industry experts to serve as advisors, Osuji said.

At Walgreens, pipeline programs engage students early and expose them to possible career paths, Smith said. The company works with Black Girls Who Code and other organizations to bring youth into Walgreens for competitions, inviting them to brainstorm solutions to real problems the company is working on, such as improving health equity.

“When you’ve got folks who’ve been staring at a problem for so long, and you bring bright minds in to solve a real-world problem with their perspective, it builds confidence,” Smith said. “And it heightens the curiosity in those individuals, so we do a lot with actually putting people with people and inspiring an individual and a program at a time.”

Startups themselves have to be intentional about recruiting Black tech talent.

Even at Five to Nine, which is founded by two Black women, Shells said it is not enough to put out a job description and hope diverse applications to pour in. She searches for diverse candidates through platforms like Hired and LinkedIn and asks people in her network to recommend someone.

For Osuji, who cofounded his company with another Black man, it was important that the next two hires be women. He ended up investing more than he thought he would have to in the hiring hunt to ensure he was casting a net beyond his circle, as he believes innovation benefits from differences in opinion.

Another way to build diverse teams is to shift the focus from finding the right person for a job to finding a job for the right person, Brand said. Even if there isn’t an open position, it may be worth making opportunistic hires and creating a role for an exceptional candidate.

Chicago’s unique startup community – and what it lacks

Brand, who is based in San Diego and travels often to startup meccas including New York and the Bay Area, said the support system behind Chicago’s startup ecosystem is impressive and singular.

“I have never seen so many organizations focused on the startup community,” said Brand. “Also diversity is huge and there’s continued support not only for startups but for the companies trying to support and help these startups. The ecosystem is consistently growing.”

But when it comes to fundraising, Chicago startups struggle in their early rounds.

Checks in the Midwest tend to be smaller than on the coasts, so Chicago founders have to be willing to travel and expand their network to find capital, Osuji said.

That reality is what prompted Shells to move her company from Chicago to New York. While Chicago’s angel investors are unparalleled – “They will go to the mountaintop and shout about their portfolio,” Shells said – she struggled to raise a seed round.

But once she accomplished that milestone, she moved back, bullish about building the company in Chicago even if she needed New York money to get it off the ground.

“We could have stayed in New York, we could have gone to SF, but I’m a huge believer that we need more examples here of Black women who are kicking butt, who are doing it,” she said.

Shells, who expects to close her next round soon, has been heartened to see other founders recommit to Chicago, some establishing their own venture funds dedicated to supporting Black and diverse entrepreneurs.

Black founders are “over-mentored and under-funded,” Shells said, so the greatest support Chicago’s startup ecosystem could offer is to write more checks. Also needed is help finding and hiring great, diverse talent, she said.

Some organizations are offering funding alternatives to venture capital.

Brand’s organization, which focuses on supporting under-represented entrepreneurs, offers debt financing so that founders don’t have to give up equity. It doesn’t look at personal credit scores, but how the business is run.

Fundraising advice for aspiring founders

Despite the challenges, it is a good time for Chicago-based startups to raise money because the virtual environment has erased geographic barriers, making it easier to pitch to VCs on the coasts, Shells said.

She advises founders to practice pitching to funds that they don’t really want as investors, so that they know what questions to expect when the stakes are higher. In addition, she said, understand that a long “maybe” probably means “no,” but a “no” can mean “not yet.”

To Osuji, an important part of fundraising is having a solid business to invest in. He started Eventnoire, which lists events where Black people and culture are “celebrated not just tolerated,” after years working in event planning, and was earning revenue on Day 1.

“An investment is expected to help you accelerate, but you have to build a business whose economic units make sense,” he said.

Article by Alexia Elejalde-Ruiz, associate director of media relations and external communications at the Polsky Center. A longtime journalist, Alexia most recently was a business reporter with the Chicago Tribune. Reach Alexia via email or on Twitter @alexiaer.